How we make npm packages work in the browser

We upgraded our npm support to be 99.98% cheaper and 2,000% faster using serverless.

I always left npm dependency support out of scope during initial development of CodeSandbox. I thought it would be impossible to install an arbitrary, random amount of packages in the browser, even thinking about it caused my brain to block.

Nowadays npm support is one of the most defining features of CodeSandbox, so somehow we succeeded in making it work. It took a lot of iterations to make it work in any scenario, we did multiple rewrites and even now we can still improve the logic. I'll explain how npm support started, what we have now and what we still can do to improve it.

'First' Version

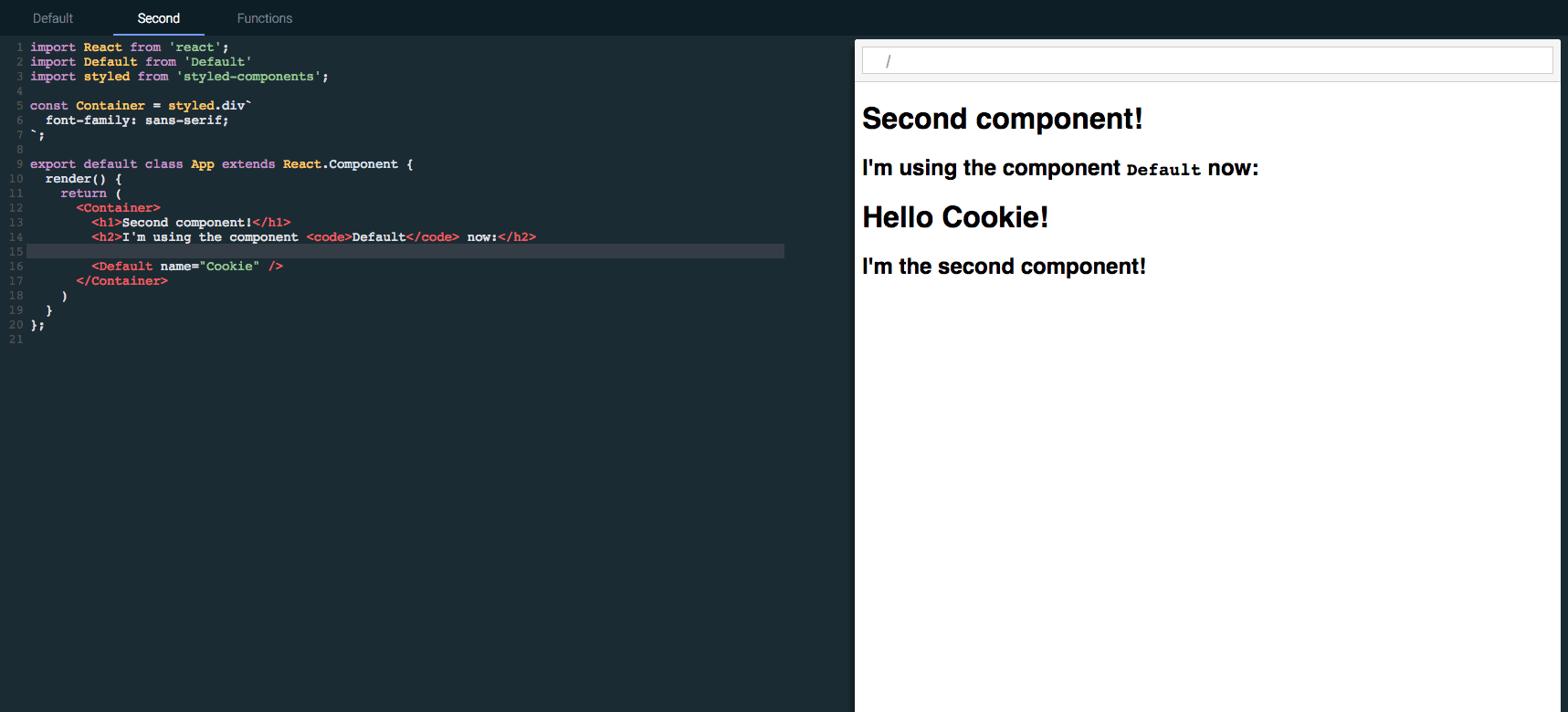

I really didn't know how to approach this, so I started with a very simple version of npm support:

This version of npm support was very simple. It wasn't even really npm support, I just installed the dependencies locally and stubbed every dependency call with an already installed dependency. This, of course, is absolutely not scalable to 400,000 packages with different versions.

Even though this version was not very usable, it was encouraging to see that I was able to at least make two dependencies work in a sandbox environment.

webpack Version

I was quite satisfied with the first version, and I thought it would be

sufficient for an MVP

(the first release of CodeSandbox). I didn't think it would be even possible to

install any dependency without performing magic. That was until I stumbled upon

https://esnextb.in. They already

supported any dependency from npm, you could just define them in package.json

and it magically worked!

This was a big learning moment for me. I never dared to give proper npm support a thought, because I thought 'it would be impossible'. Only after seeing living proof of its 'possibleness' I started putting more thought into it. I should've explored the possibilities first before dismissing the idea.

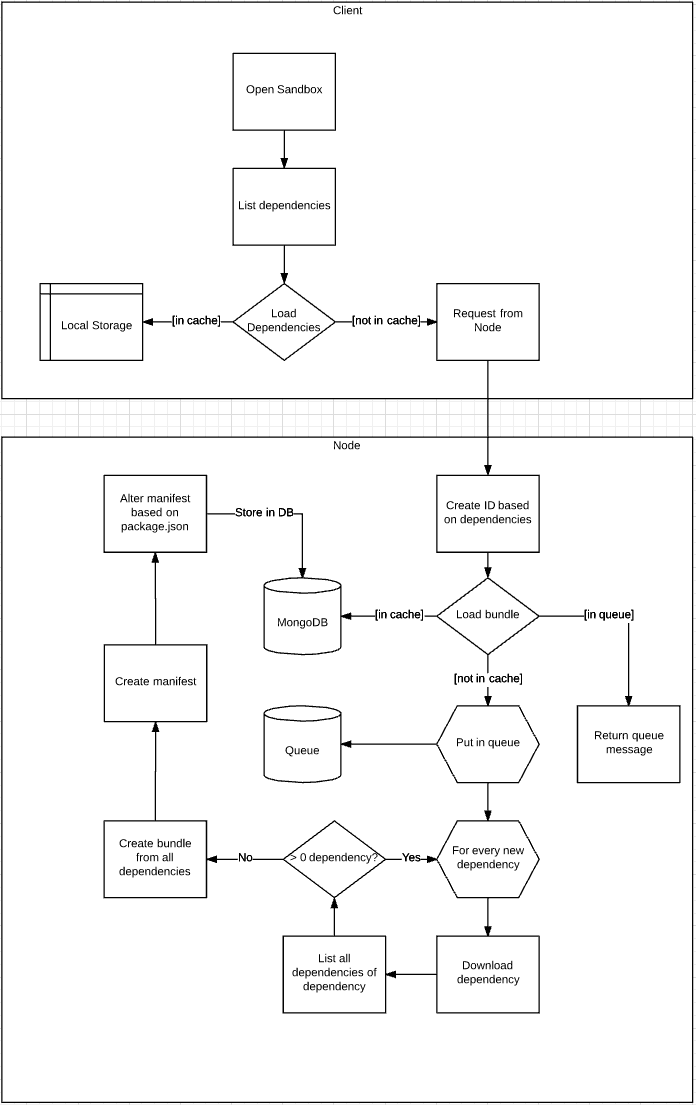

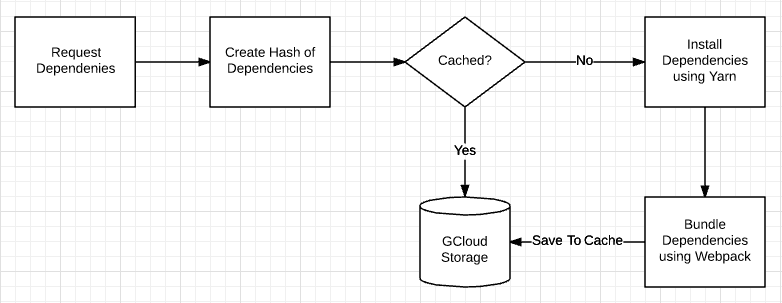

So! I started thinking on how to approach this. And boy did I overcomplicate it. My first version didn't fit in my head, so I had to draw a diagram:

There was one advantage of this overcomplicated approach: the actual implementation was much easier than expected!

I learned that webpack's

DllPlugin was able to bundle

dependencies and spit out a JS bundle with a manifest. This manifest looked like

this:

{

"name": "dll_bundle",

"content": {

"/node_modules/fbjs/lib/emptyFunction.js": 0,

"/node_modules/fbjs/lib/invariant.js": 1,

"/node_modules/fbjs/lib/warning.js": 2,

"/node_modules/react": 3,

"/node_modules/fbjs/lib/emptyObject.js": 4,

"/node_modules/object-assign/index.js": 5,

"/node_modules/prop-types/checkPropTypes.js": 6,

"/node_modules/prop-types/lib/ReactPropTypesSecret.js": 7,

"/node_modules/react/cjs/react.development.js": 8

}

}Every path is mapped to a module id. If I would require

React I would only have to call dll_bundle(3) and I would

get React! This was perfect for our use case, so I started typing away and came

up with this actual system:

For every request to the packager I would create a new directory in

/tmp/:hash, would run yarn add ${dependencyList} and let webpack bundle

afterwards. I'd save the new bundle on

gcloud as a way of caching. Much simpler

than the diagram, mostly because I replaced installing dependencies with

yarn and bundling with webpack.

When you load a sandbox, we would first make sure that we'd have the manifest

and the bundle before evaluation. During evaluation we would call

dll_bundle(:id) for every dependency. This worked very well, and I got my

first version with proper npm dependency live!

Now there was still a big limitation with this system. It didn't support files

that were not in the dependency graph of webpack. This means that for example

require('react-icons/lib/fa/fa-beer') wouldn't work, because it was never

required by the entry point of the dependency in the first place.

I did release CodeSandbox with this version though, and got in contact with the author of WebpackBin Christian Alfoni. We used a very similar system to support npm dependencies and we were having the same limitations. So we decided to combine forces and build the ultimate packager!

webpack with entries

The "ultimate" packager retained the same functionality as our previous

packager, except Christian created an

algorithm that would add files to the bundle depending on their importance. This

means that we manually added entry points, to make sure that webpack would

bundle those files too. After a lot of tweaking of this system we got it working

for any(?) combination. So you were able to require

react-icons, and CSS files as

well 🎉.

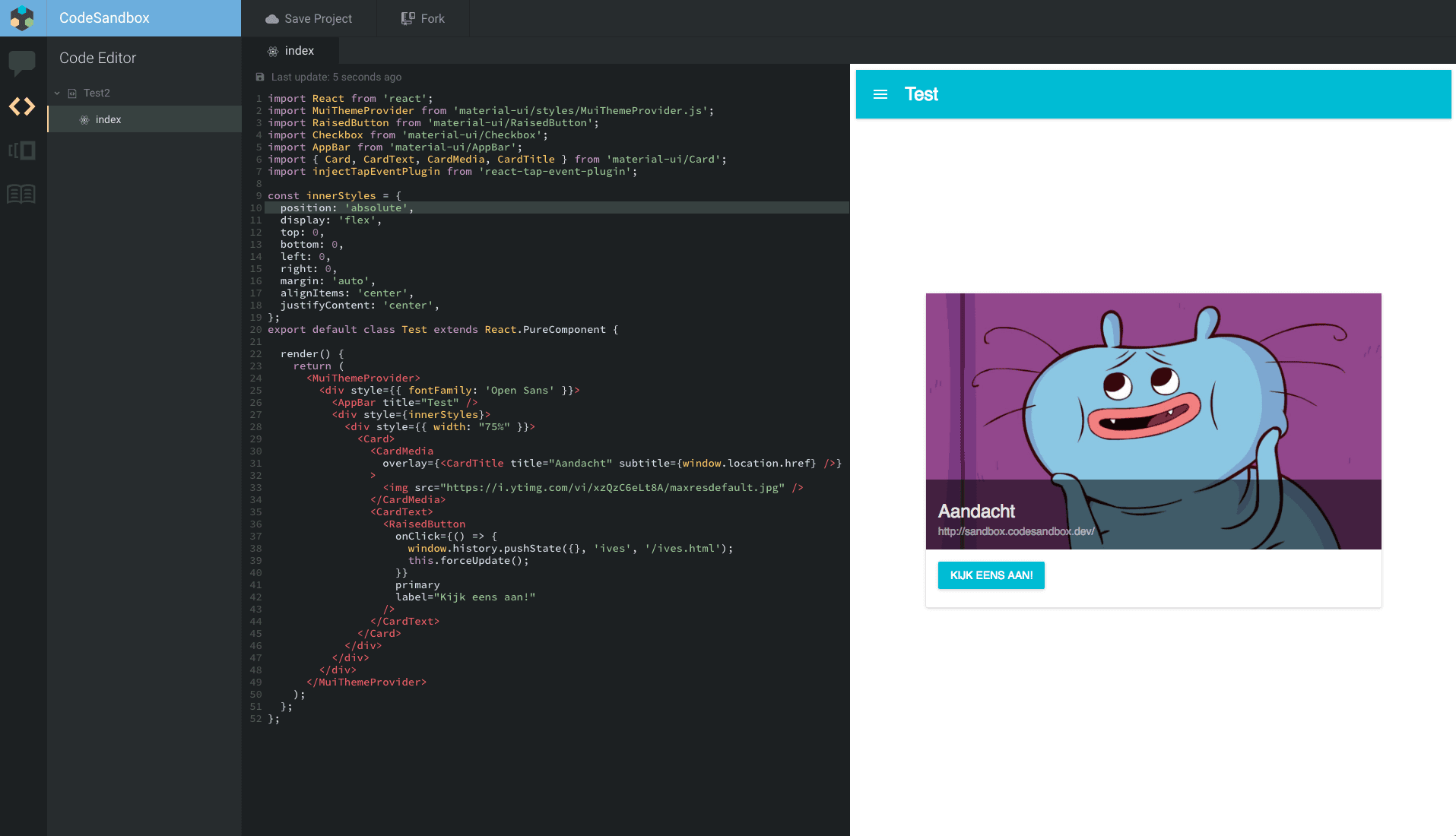

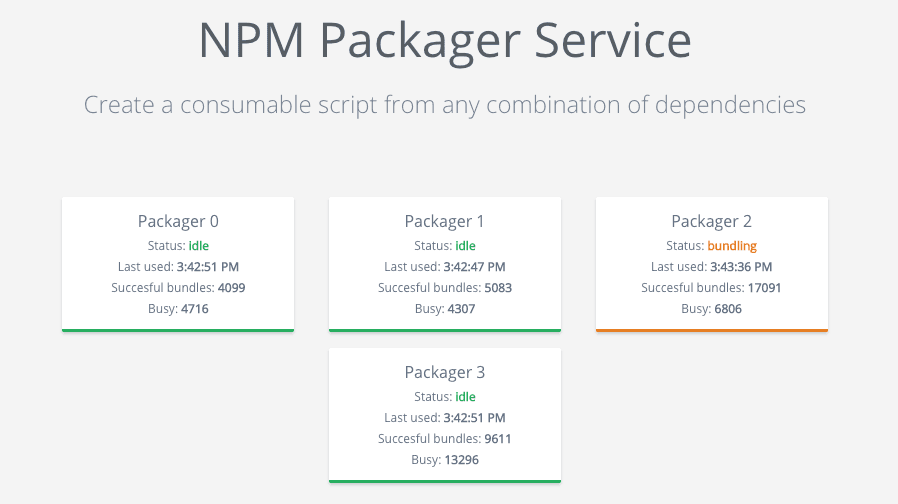

The new system also got an architectural upgrade: we have one DLL service that serves as load balancer and cache. Then we have multiple packagers that do the bundling, these packagers can be dynamically added.

We wanted to make the packager service available for everyone. That's why we built a website that would explain how the service works and how you can make use of it. This turned out to be a great success, we were even mentioned in the CodePen blog!

There were still some limitations and disadvantages to this 'ultimate' packager. The costs grew exponentially as we became more popular, and we were caching by package combination. Which means that we had to rebundle your whole package combination if you added a dependency.

Going Serverless

I always wanted to try this cool technology called 'serverless'. With serverless you can define a function that will execute on request, the function will spin up, handle the request and then kill itself after some time. This means that you have very high scalability: if you get 1000 simultaneous requests you can just spin up 1000 servers instantly. It also means that you only pay for the time the servers actually run.

Serverless sounds perfect for our service: it doesn't run fulltime and we need high concurrency in case there are multiple requests at the same time. So I started playing eagerly with an aptly named framework called Serverless.

Converting our service went smoothly (thanks Serverless!), I had a working version within 2 days. I created three serverless functions:

- A metadata resolver: this service would resolve versions and peerDependencies and request the packager function.

- A packager: this service would do the actual installing & bundling of the dependencies

- An uglifier: responsible for asynchronously uglifying the resulting bundle.

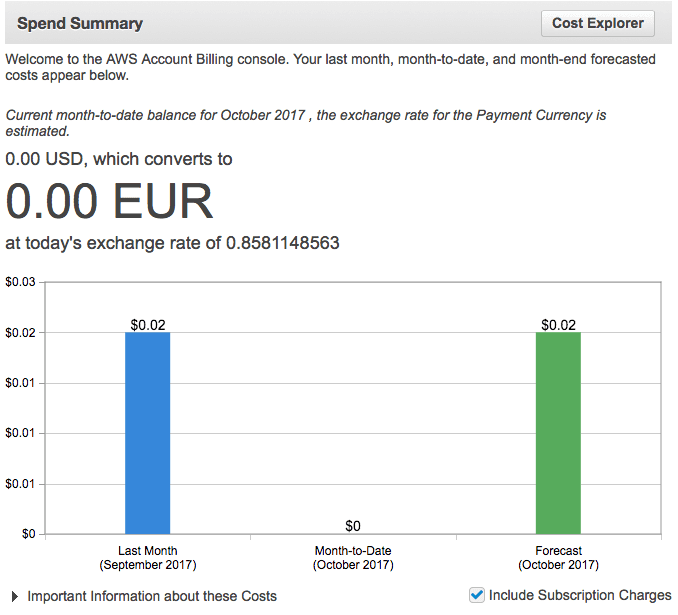

I ran the new service alongside the old service, and it worked really well! We had a projected cost of $0.18 per month (compared to $100) and our response time improved between 40% and 700%.

After several days I started noticing a limitation though: a lambda function only has 500MB of maximum disk space, this means that some combinations of dependencies weren't able to install. This was a deal breaker and I had to get back to the drawing board.

Serverless Revisited

A couple months went by and

I released a new bundler for CodeSandbox.

This bundler is very powerful, and allows us to easily support more libraries

like Vue and Preact. By supporting these

libraries we got some interesting requests. For example: if you want to use a

React library in Preact, you'd need to alias

require('react') to require('preact-compat'). For Vue, you may want to

resolve @/components/App.vue to your sandbox files. Our packager doesn't do

this for dependencies, but our bundler does.

That's when I started thinking that we could maybe let the browser bundler do the actual packaging. If we would just send the relevant files to the browser we'd let the bundler do the actual bundling of the dependencies. This should be faster, because we're not evaluating the whole bundle, just parts of it.

There is a great advantage to this approach: we will be able to install and

cache dependencies independently. We can just merge the dependency files on the

client. This means that if you request a new dependency on top of your existing

dependencies, we'd only need to gather files for the new dependency! This will

solve the 500MB limit from AWS Lambda, since

we're only installing one dependency. We can also drop webpack from the

packager, since the packager now has the sole responsibility of figuring out

which files are relevant and sending them.

Note: We could also drop the packager and request every file dynamically from unpkg.com. This is probably even faster than my new approach. I decided to still keep the packager (at least for the editor), because I want to provide offline support. That's only possible if you have all possible relevant files with you.

How it works in practice

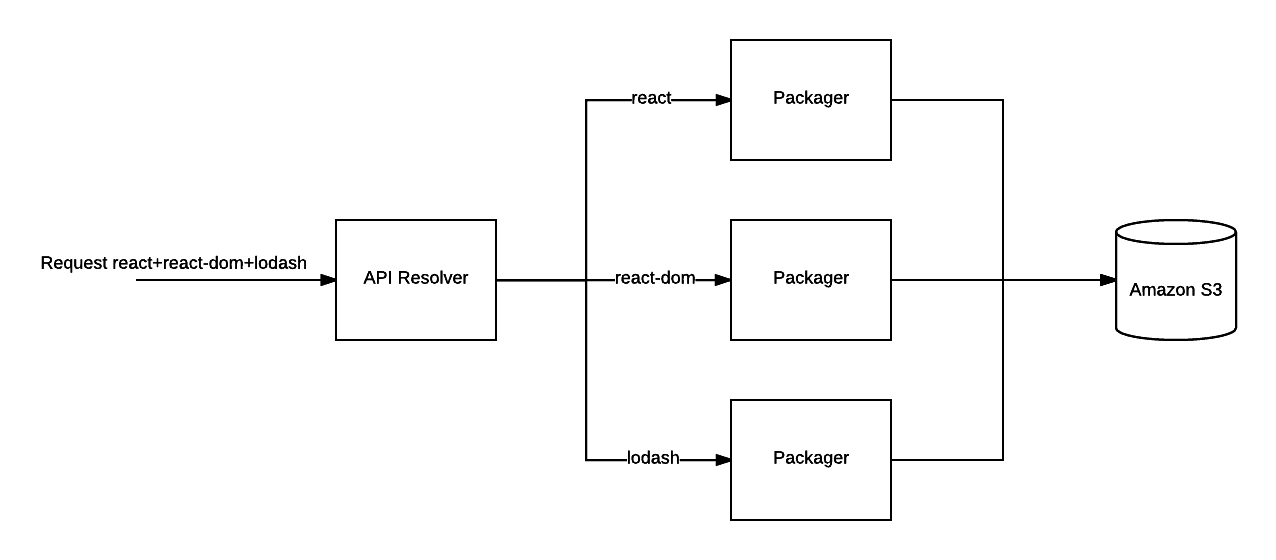

When we request a combination of dependencies, we first check if this combination already is stored on S3. If it's not on S3 we request the combination from the API service; this service requests all packagers independently for every dependency. As soon as we get the 200 OK back, we request S3 again.

The packager installs the dependencies using yarn and finds all relevant files

by traversing the AST of

all files in the directory of the entry point. It searches for require

statements and adds them to the file list. This happens recursively, so we get a

dependency graph. An example output (of react@latest) is this:

{

"aliases": {

"asap": "asap/browser-asap.js",

"asap/asap": "asap/browser-asap.js",

"asap/asap.js": "asap/browser-asap.js",

"asap/raw": "asap/browser-raw.js",

"asap/raw.js": "asap/browser-raw.js",

"asap/test/domain.js": "asap/test/browser-domain.js",

"core-js": "core-js/index.js",

"encoding": "encoding/lib/encoding.js",

"fbjs": "fbjs/index.js",

"iconv-lite": "iconv-lite/lib/index.js",

"iconv-lite/extend-node": false,

"iconv-lite/streams": false,

"is-stream": "is-stream/index.js",

"isomorphic-fetch": "isomorphic-fetch/fetch-npm-browserify.js",

"js-tokens": "js-tokens/index.js",

"loose-envify": "loose-envify/index.js",

"node-fetch": "node-fetch/index.js",

"object-assign": "object-assign/index.js",

"promise": "promise/index.js",

"prop-types": "prop-types/index.js",

"react": "react/index.js",

"setimmediate": "setimmediate/setImmediate.js",

"ua-parser-js": "ua-parser-js/src/ua-parser.js",

"whatwg-fetch": "whatwg-fetch/fetch.js"

},

"contents": {

"fbjs/lib/emptyFunction.js": {

"content": "/* code */",

"requires": []

},

"fbjs/lib/emptyObject.js": {

"content": "/* code */",

"requires": []

},

"fbjs/lib/invariant.js": {

"content": "/* code */",

"requires": []

},

"fbjs/lib/warning.js": {

"content": "/* code */",

"requires": ["/emptyFunction"]

},

"object-assign/index.js": {

"content": "/* code */",

"requires": []

},

"prop-types/checkPropTypes.js": {

"content": "/* code */",

"requires": [

"fbjs/lib/invariant",

"fbjs/lib/warning",

"/lib/ReactPropTypesSecret"

]

},

"prop-types/lib/ReactPropTypesSecret.js": {

"content": "/* code */",

"requires": []

},

"react/index.js": {

"content": "/* code */",

"requires": ["/cjs/react.development.js"]

},

"react/package.json": {

"content": "/* code */",

"requires": []

},

"react/cjs/react.development.js": {

"content": "/* code */",

"requires": [

"object-assign",

"fbjs/lib/warning",

"fbjs/lib/emptyObject",

"fbjs/lib/invariant",

"fbjs/lib/emptyFunction",

"prop-types/checkPropTypes"

]

}

},

"dependency": {

"name": "react",

"version": "16.0.0"

},

"dependencyDependencies": {

"asap": "2.0.6",

"core-js": "1.2.7",

"encoding": "0.1.12",

"fbjs": "0.8.16",

"iconv-lite": "0.4.19",

"is-stream": "1.1.0",

"isomorphic-fetch": "2.2.1",

"js-tokens": "3.0.2",

"loose-envify": "1.3.1",

"node-fetch": "1.7.3",

"object-assign": "4.1.1",

"promise": "7.3.1",

"prop-types": "15.6.0",

"setimmediate": "1.0.5",

"ua-parser-js": "0.7.14",

"whatwg-fetch": "2.0.3"

}

}Advantages

Save in cost

I've deployed the new packager two days ago, we paid a whopping $0.02 for those two days! And this was for building up the cache. This is a huge saving compared to $100 a month.

Higher performance

You can now get a new combination of dependencies within 3 seconds, for any combination. With the old system this sometimes would take a minute. If the combination is cached you'll get it within 50ms on a fast connection. We cache the dependencies using Amazon Cloudfront all over the world. Our sandbox also runs faster, because we now only parse and execute the relevant JS files for your sandbox.

More flexibility

Our bundler now handles the dependencies as if it were local files. This means

that our error stack traces are now much clearer, we can now include any file

from dependencies (like .scss, .vue, etc.) and we can easily support things

like aliases. It works just as if the dependencies are installed locally.

Release

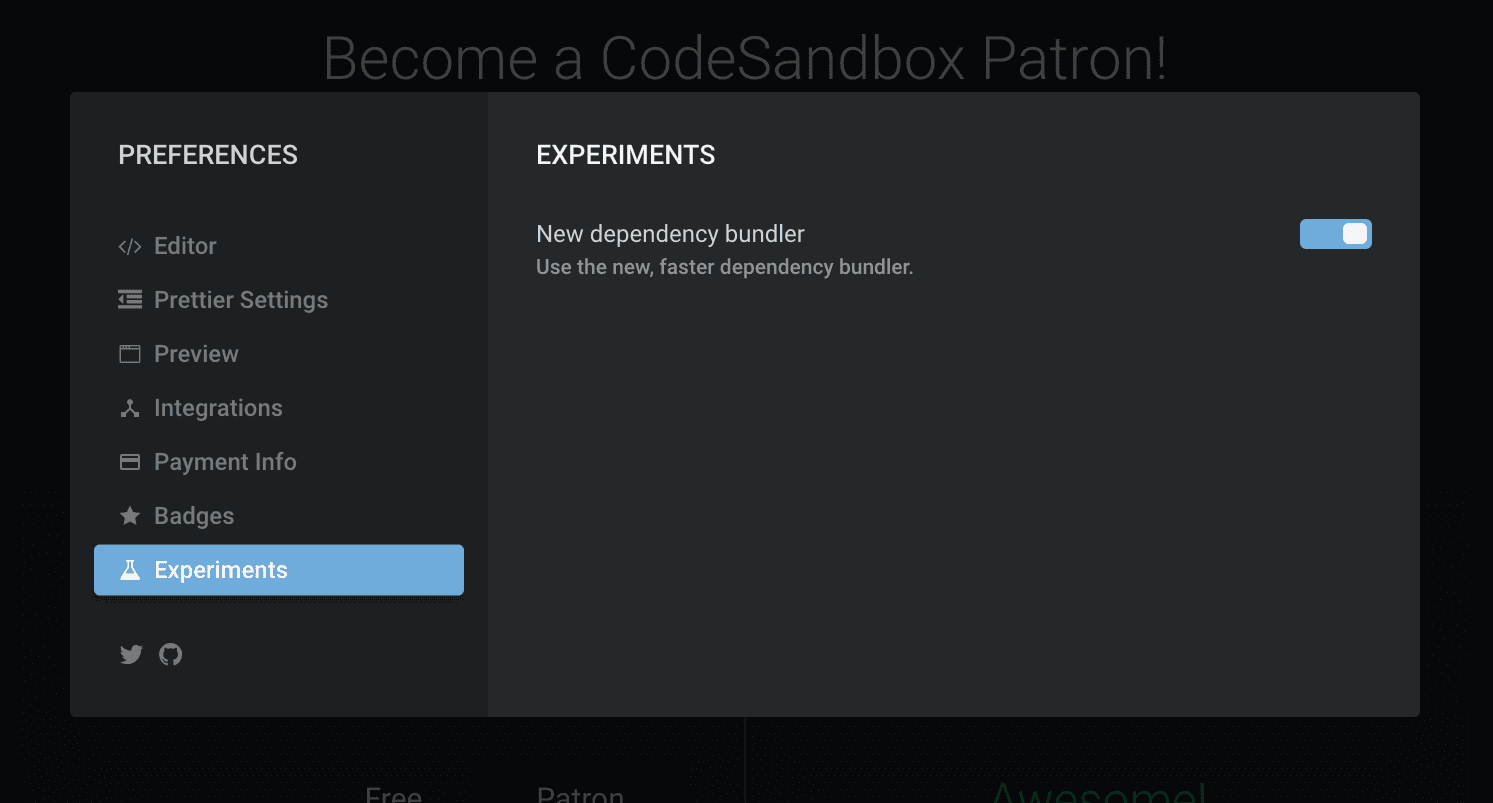

Two days ago I started using the new packager alongside the old packager, to build up cache. It already cached 2,000 different combinations and 1400 different dependencies. I want to test the new version extensively before actually moving over. You can try it today by enabling it in your preferences!

Also, if you're interested in the source, you can find it here.

Go Serverless!

I am very impressed by serverless, it makes server scalability and management incredibly easy. The only thing that always held me back from serverless is the very complicated setup, but the people at serverless.com made this child's play. I'm very grateful for their work, I do think that serverless is the future for many different application forms.

Future

We can still improve the system in a lot of ways, I'm eager to explore dynamically requesting requires in embeds and preserving offline. It's a hard balance to keep, but it should be possible. We can also start caching dependencies independently in the browser, depending on what the browser allows. In that case you sometimes don't even need to download new dependencies when visiting a new sandbox with different dependency combination. I'm also going to explore dependency resolution more, there is a chance of conflicting versions with the new system which I want to solve before going full on.

Nevertheless I'm very happy with the new version, onwards to working on new things for CodeSandbox!

If you're interested in CodeSandbox, we're 90% open source! The most activity is here.